By Ena Mulavdic

Miniature art boasts a history that stretches back to prehistoric times, originating from carved gemstones. This art form has a rich and diverse heritage, having been used for a multitude of purposes across various historic epochs and regions around the world. Just as the history of painting is vast and intricate, so too is the history of miniature painting, filled with beauty, profound symbolism, and masterfully crafted artworks. These miniatures showcase exceptional skill in composition, color, motifs, and symbolic meaning, standing as a testament to the enduring appeal and significance of this art form.

For decades, miniatures have been revered as an exceptional art form. The intricate details, precise composition, and often vibrant, exquisite colors are hallmark characteristics of miniature paintings, making their value indisputable when compared to large-scale works. Despite their small size, one of the most remarkable features of miniatures is the meticulous brushwork, which adds to their uniqueness. Techniques such as hatching, stippling, pointillism, and other fine details often require magnification to be fully appreciated.

Interestingly, the etymology of the word "miniature" is rooted not in size, but in color. The term derives from the Latin word "minium," which refers to the red lead used by medieval artists to embellish the initial letters in illuminated manuscripts (see figure 1). This red pigment, known as "minium," was among the earliest colors employed to decorate these initial letters, highlighting the importance of color in the origins of the term.

Figure 1. “Minium” or red lead as mineral and as pigment

This unique art form has its origins in the book paintings and illuminated manuscripts of 7th-century India. An illuminated manuscript refers to a document in which the text is adorned with miniature illustrations and/or decorative borders. This technique is commonly found in religious texts, as well as in nonreligious literature, proclamations, inventories, deeds, laws, and enrolled bills.

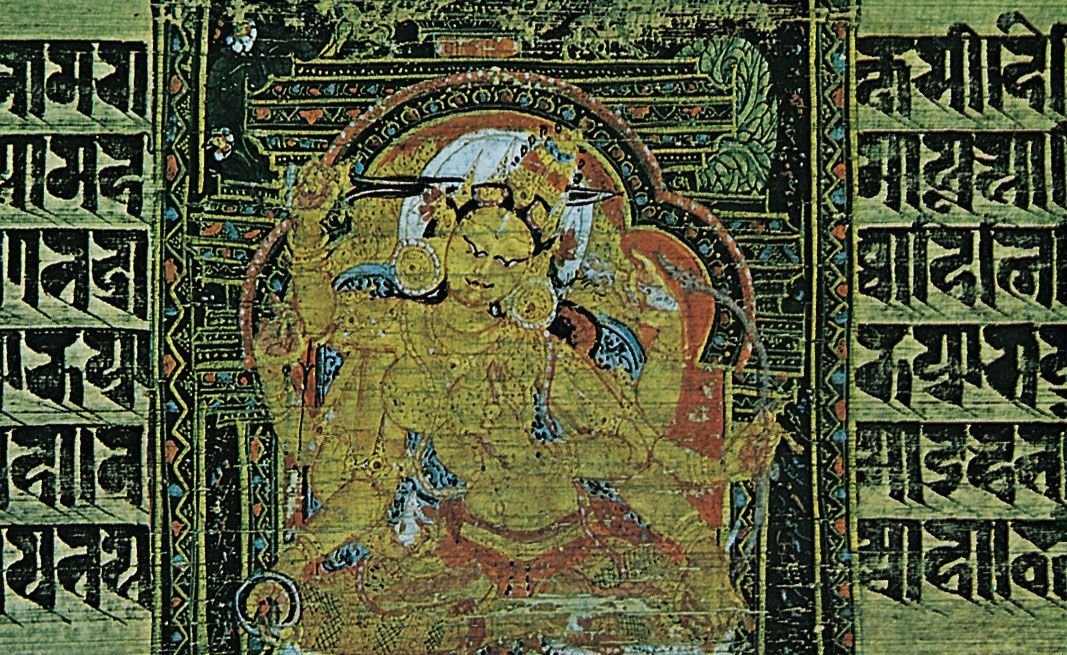

Palm leaves were the most commonly used medium for these works, with Buddhist texts and scriptures often inscribed on them. Due to the limited space on palm leaves, the illustrations had to be miniature in size. This form of miniature painting is known as Pala art (see figure 2), and it is distinguished by its graceful lines and soft, subtle colors.

Figure 2. A Buddhist divinity, painting on palm leaf, Pala period, c. 12th century; in a private collection.

The Islamic world is renowned for its deep appreciation of the art of miniature painting. This intricate art form flourished across the Middle East, Central Asia, and Far Eastern regions, particularly in Persia, India, the Ottoman Empire, and other Eastern countries. Miniature paintings, often used to illuminate manuscripts, were a well-established tradition in these regions even before the year 1400.

The 15th century saw the introduction of Persian influences, which brought about a significant shift in materials, replacing the fragile palm leaf with paper. This change allowed for greater detail and complexity in miniature art, with scenes of hunting and diverse facial expressions becoming more common. The use of gold and aquamarine blue hues also became prominent during this period.

Miniature art in India reached its zenith under the Mughal Empire (16th-18th century A.D.), marking a rich and vibrant era in the history of Indian art. The Mughal style of painting was a harmonious blend of religion, culture, and tradition (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Unknown artist, Prince With a Falcon, 1600-1605. Courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Persian miniatures, in contrast, were heavily influenced by Chinese artisans. This connection is evident from the fact that paper itself was introduced to Persia from China in 753 A.D. The Mongol rulers of Persia further strengthened this influence by bringing the tradition of Chinese painting and welcoming many Chinese artisans who migrated to Persia.

Persian miniatures are distinctive for their close relationship with literary works. They often served as visual interpretations of literary plots, enhancing the understanding and enjoyment of both the visual and literary elements. In many ways, Persian miniatures can be seen as visual poetry, merging imagery with narrative to create a rich, immersive experience.

One of the most notable examples of Persian miniatures is the epic poem "Shahnameh" by Ferdowsi (see figure 4), which narrates the history of Persia from the creation of the world to the Arab conquests in the 7th century.

Figure 4. Qam - Persian miniature taken from Shahnameh by the great Iranian poet Ferdowsi, 1591.

Another significant factor contributing to the flourishing of miniature art in Persia, especially during the Islamic era, was related to Islamic aniconism. While Islamic tradition generally prohibits the depiction of religious figures to avoid idolatry, exceptions can be found in some manuscripts from regions east of Anatolia, such as Persia and India. These illustrations, including depictions of the Prophet Muhammad—sometimes with his face concealed (see figure 5)—and other religious figures, were intended to complement the narrative rather than violate Islamic prohibitions.

The Persian miniature not only thrived within its own cultural context but also became a dominant influence on other Islamic miniature traditions, particularly the Ottoman miniatures in Turkey and the Mughal miniatures in the Indian subcontinent. The impact of Persian miniature art extended beyond the Islamic world, inspiring renowned painters such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, who incorporated its aesthetic principles into their own artistic approaches.

Figure 5. An illustrated folio from a Qajar manuscript: The prophet Muhammad, Qajar Iran, 19th century

Illuminated manuscripts were highly prized throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance. However, with the invention of the printing press around 1440, printed books became strong competitors to these manuscripts. In response, artists began creating standalone miniature paintings for patrons, which were often used as devotional objects or luxury items for connoisseurs.

One of the most significant developments on the European continent was the emergence of portrait miniatures in the 16th century. These artworks evolved from illuminated manuscripts, where portraits of rulers and patrons were painted on separate pieces of vellum and later incorporated into books and official documents. French artist Jean Clouet (see figure 6) played a pivotal role in liberating these portraits from the confines of books, presenting them as freestanding, framed works of art.

This trend quickly gained popularity in England during the reign of Henry VIII. Commissioning portrait miniatures became a fashionable practice among the aristocracy, court members, the wealthy urban elite, and even the monarch and his family. These portraits were often transformed into jewellery, set in lockets, frames, or boxes, and were either worn or kept in private cabinets as treasured possessions.

A significant innovation in the 17th century further advanced the art of miniature portraits in relation to jewellery. Artist Jean Petitot introduced the technique of painting miniatures in enamel on a metal surface, a departure from the earlier practice of using watercolor on vellum or paper. This technique added durability and brilliance to miniature portraits, enhancing their appeal and versatility.

Figure 6. Jean Clouet (c.1485-90?- 1540/41), François, Dauphin of France (1518-36), c.1526, watercolour on vellum on card, 6.2 cm. diam., Royal Collection Trust/ HM Elizabeth II 2017

As new miniaturists emerged, they began to break away from the pictorial conventions of previous generations. Rather than drawing inspiration from manuscript paintings, this new generation looked to the broader developments in large-scale oil painting. Over time, miniature portraits increasingly found their way into jewellery and were often enameled. Due to their small size and portability, these miniatures served a similar purpose to photographs today. In fact, several royal marriage negotiations only proceeded after careful consideration of a miniature portrait of the prospective bride. Highly valued, miniatures were frequently exchanged as tokens of friendship, loyalty, and love.

The 18th century witnessed one of the most significant technical innovations in portrait miniature painting. Until then, vellum was the most commonly used material for supporting portrait miniatures, but it was gradually replaced by ivory (see figure 7). This shift is credited to the Venetian painter Rosalba Carriera, who popularized the use of ivory, enhancing the luminosity and delicacy of the miniatures.

Figure 7. Eliza Izard (Mrs. Thomas Pinckney, Jr., 1784–1862), 1801, by Edward Greene Malbone, American, 1777–1807); Watercolour on ivory; 2 7/8 x 2 3/8 inches;

The materials used for illustrated manuscripts and miniatures were primarily derived from animal skins, including vellum made from sheep, goat, or cow hides. The colors (see figure 8) used in these paintings were extracted from various natural sources such as vegetables, indigo, precious stones, gold, and silver. These pigments not only provided vibrant hues but also carried significant symbolic meanings in the context of miniatures. Fatima Zahra Hassan beautifully explains the intricate process of creating these colors and their symbolic significance in miniatures in the following link: click here.

Gouache and oil paints were often applied on vellum, while from the 17th century onwards, high-quality miniatures were frequently created using vitreous enamel on copper. By the end of the 18th century, the use of watercolors on ivory became increasingly common, offering a new level of delicacy and luminosity to these exquisite works of art.

Figure 8. Colour powder pigments for miniatures

One of the most cherished techniques in our jewellery design is miniature painting (see figure 9). This affinity is partly due to our Iranian heritage and partly because miniatures serve as visual storytellers, enriching our jewellery with a unique narrative quality. It's no wonder that our pieces are often described with the phrase "jewellery that tells stories." Indeed, our aim is to use jewellery as a medium to explore one of the most profound missions we have in life—understanding ourselves. As we delve deeper into self-discovery, we gain insights into the world around us and, most importantly, we achieve a sense of inner freedom, regardless of our external circumstances.

We strive to visualize these themes through the use of oil paints, primarily on enameled metal surfaces such as gold, silver, or bronze, and occasionally on paper or wooden backgrounds. Miniature painting is integral to our jewellery; it’s an inseparable part of our creative process. We begin by mixing colors to achieve the perfect hues, then apply the paint to the background. Using fine tools like needles and toothpick-like "brushes," we subtract excess paint to create delicate lines and solid color areas. Some details are crafted using the pointillism technique. Once the miniature is completed, it requires several days for the oil paint to dry before being sealed with a thin layer of transparent enamel or, more commonly, a 2mm thick faceted watch glass. Occasionally, we also create miniatures within gemstones, using either the negative painting technique or a traditional approach.

In essence, the art of miniatures, encompassing illuminated manuscripts and jeweled miniatures, represents a vast and rich field of artistic, literary, and scientific exploration. Through this medium, the history of humankind can be beautifully narrated and visually explained.

Figure 9. Miniature oil paintings on ceramic by ELIRD, 2018

Disclaimer: ELIRD does not own any of these images, excluding eight (8) images on Figure 9. Please note that all images and copyrights belong to their original owners. no copyright infringement intended.